The Conceptual Triad

[jibaro house on eroded tobacco slope in Puerto Rico, 1938 by Edwin Rosskam; the field has its own form, its effect on the slope, the river below, the house above, viewers from the next hill over, and it takes part in a larger farming landscape; in this way it can be understood as an instrument in the farming landscape]

Within a theory of landscape instrumentalism it is necessary and possible to probe just what an instrument is. If an instrument is any entity understood to exist at the intersection of perception and reality, and these entities make up a landscape, then how might they be conceptualized? From Harman we learn that any instrument that is perceived is but a sliver of the object reality of that instrument, that it always maintains something in reserve and that this is always present.

I’ve stated that a working theory of landscape instrumentalism suggests a need for more specificity, for techniques that allow us to grapple with the autonomy and potency, the generative capacity, of things themselves in the landscape, and not just human users. At first glance this might seem futile at best, dastardly at worst; an attempt to categorize and over-analyze all of the living, breathing objects that comprise the fantastic landscapes where we live our lives. It rings of the negative connotation conjured by recent theorists who lambast any notion of objectification and deride scientific or analytical attempts to grapple with things. However, Harman again uses Heidegger to show that this is far from the truth when he states that “the [tool] continues to sustain its [tool]-effect, no matter how obtrusively analyzed or how directly perceived it might be in any specific case. In short, to engage in ever more explicit encounters with specific objects does not entail negating or rising beyond the cryptic tool-being of these things.”

Instead, I would suggest that as persons tasked with a conceptualizing and important role in the creation of specific types of landscapes considered to be of great value (a new neighborhood park, parking lot, or corporate garden) we must develop techniques that allow us to grapple with a range of entities in conceptual terms. In recent decades the map has achieved a sort of hegemony in terms of landscape architectural practice, reinforced by flow diagrams and claritin drawings. James Corner has argued persuasively that the map is not a representational technique but is generative, and the work of Bradley Cantrell and others is pointing a way toward new methods of modeling, which are more than mere representation but are actually modalities of translation. This is what technique is and should be- a constant search for appropriate modalities that allow us to translate the forces of objects and their relations to other objects.

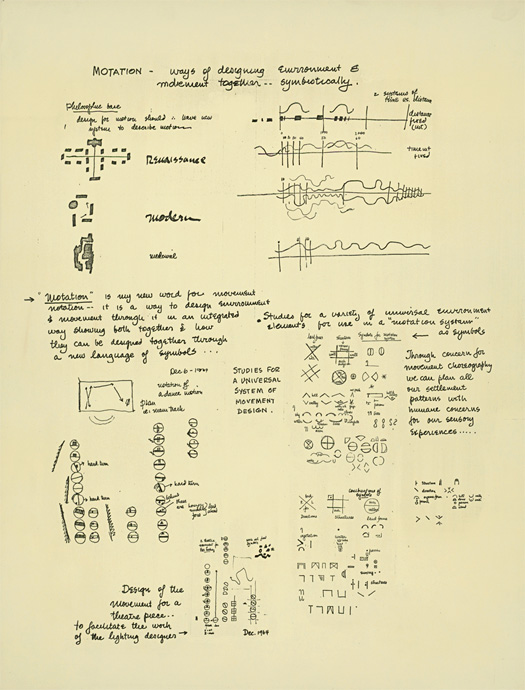

[a drawing from Halprin’s “motation” studies, developing notational techniques to examine the way that people move through a landscape and create space]

To achieve this it is important to understand the instrument as consisting of a conceptual triad: form, effect, and the assemblage it takes part in. The form of an instrument pertains to its shape, its effect can be understood as its relations to other objects. The final leg of the stool is related to the effect and is particular to landscapes. The assemblage something takes part in refers to the larger activity or set of actions that is tied to but related to a certain object at a particular time. For instance at a recreational lake there may be several boating docks and many paddle boats, along with the water in the lake and human users. All of these objects are part of the same program activity- the boating assemblageat the lake- but not all of them relate to one another at the same time. This difference among things is important, this separation of levels, because it allows for more specificity in the design of the space.

One technique that I favor for exploring this conceptual triad is the use of multiple sections, cut through the same place but at different times. Speculative or not, this simple maneuver allows one to examine the changes in arrangements of objects and their relations over time: the forest is similar but the leaves have changed color, the water level in the canal is higher, there are more people in boats or on the boardwalk, birds are nesting in the high grasses or not. The weakness to this technique of using sections is the primacy on form. There is a need to develop techniques to be explicit about the full triad in the same way that the section allows us to be about form.

[here stacked orthographic sections indicate the shifting forms of the Riachuelo Canal landscape; these forms provide the basis to key in the instrument tables which are explicit about the effects of the individual instruments; the correlation wheel in the upper right hand corner allows for a general, color-coded indication of different program activities; in a next iteration these might be made to correspond to a color table attached to each instrument table to indicate the larger program activities for each instrument]

The key for my project, drawing from Halprin’s work, then seems to be to develop a notational system that will allow the designer to be highly specific about the conceptual triad: the form, the effect, and the larger assemblage. The current results of this effort can be seen above and are explained in more detail over on the tumblr site here, here and here.

Your focus on the section ties in with this recent essay articulating the usefulness of the “deep section” by the folks over at landscape urbanism

http://landscapeurbanism.com/article/the-performative-ground/4/

It seems in some way to be a remove away from map but still highly diagrammatic…